DNA-Schaden

Ein DNA-Schaden oder eine DNA-Schädigung ist eine Änderung der chemischen Struktur von DNA, die im Zuge der Replikation nicht mitkopiert wird.[1]

Eigenschaften

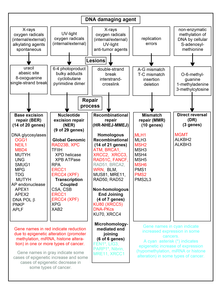

Ein Schaden an der DNA führt zu einer Aktivierung der DNA-Reparatur, um den vorherigen Zustand wiederherzustellen. Da jedoch nicht jede Reparatur den ursprünglichen Zustand wiederherstellt, können durch Schäden an DNA Mutationen erzeugt werden, die in bestimmten Kombinationen zur Entstehung von Krebs führen, z. B. wenn die Mutationen zu einer Aktivierung von Onkogenen oder zu einer Inaktivierung von Tumorsuppressorgenen führt. In gesunden Zellen können DNA-Schäden über das Protein p53 zu einem Arrest der Zellteilung und zur Apoptose führen, wodurch die Mutationsrate in einem Organismus begrenzt wird.

Entstehung

DNA-Schäden können durch ionisierende Strahlung (z. B. UV,[2] Röntgen, Gammastrahlung), Oxidation, Hydrolyse, Mutagene (darunter die Alkylanzien und DNA-Vernetzungmittel) entstehen. Durch eine Insertion von manchen Onkoviren in das Genom ihrer Wirtszelle können Gene verändert werden. Teilweise entstehen zudem Fehler in einer DNA-Sequenz durch Fehler bei der Replikation. Schäden können sowohl an den Nukleinbasen als auch am DNA-Rückgrat (Desoxyribose und Phosphat) auftreten. In einer Säugetierzelle entstehen etwa 60.000 DNA-Schäden pro Tag.[1] Ionisierende Strahlung führt durch eine Radiolyse von Wasser zur Bildung von Hydroxid-Radikalen, die andere Moleküle in ihrer jeweiligen näheren Umgebung oxidieren können. Daneben können manche DNA-Schäden auch im Zuge des Stoffwechsels ohne Einwirkung von außen (endogen) entstehen.

Durch UV-Strahlung kann es zu direkten Veränderungen (Mutationen) der DNA kommen,[2] wobei diese insbesondere UV-C-FUV-Strahlung absorbiert. Einzelsträngige DNA zeigt ihr Absorptionsmaximum bei 260 nm. Sowohl UV-B als auch UV-A können indirekt die DNA durch die Entstehung von reaktiven Sauerstoffradikalen schädigen, die die Entstehung von Oxidativen DNA-Läsionen bewirken, die wiederum zu Mutationen führen. Diese sind vermutlich für die Entstehung von UV-A-induzierten Tumoren verantwortlich.[3]

| Endogener DNA-Schaden | Anzahl pro Zelle |

|---|---|

| Abasische Stellen | 30,000 |

| N7-(2-Hydroxethyl)guanin (7HEG) | 3,000 |

| 8-Hydroxyguanin | 2,400 |

| 7-(2-Oxoethyl)guanin | 1,500 |

| Formaldehyd-Addukte | 960 |

| Acrolein-desoxyguanin | 120 |

| Malondialdehyd-desoxyguanin | 60 |

In Ratten nimmt die Anzahl abasischer Stellen von etwa 50.000 pro Zelle in Leber, Niere und Lunge bis hin zu etwa 200.000 pro Zelle im Gehirn zu.[5] In jungen Ratten sind etwa 24.000 DNA-Addukte pro Zelle, während in alten Ratten 66.000 DNA-Addukte pro Zelle zu finden sind.[6] Die Zunahme an Mutationen ist charakteristisch für das Altern.

Typen

Photocyclisierung

Bei Bestrahlung mit UV-Licht reagieren benachbarte Thymine über eine 2+2-Cycloaddition, die gleichzeitig eine Photodimerisierung und eine Photocyclisierung darstellt.

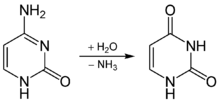

Desaminierung

Desaminierte Nukleinbasen sind Hypoxanthin, Xanthin, Uracil und Thymin, die durch Desaminierung der exozyklischen Basen Adenin, Guanin, Cytosin bzw. 5-Methylcytosin (5-mC) entstehen.[7]

Oxidation

Oxidierte DNA-Basen sind Formamidopyrimidin-Derivat von Adenin (Fapy-A), 7,8-Dihydro-8-oxoguanin (8-oxo-G) und Thymin-Glykol.[7] Etwa 60 bis 70 % der DNA-Schäden in Säugetierzellen entstehen durch Oxidation.[8] Es wurden bisher mehr als 100 Oxidationen an DNA beschrieben, von denen die Oxidation zu 8-oxodG etwa 5 % der Oxidationsschäden ausmacht.[9] Oxidationen erzeugen etwa 10.000 bis 11.500 Schäden pro Tag pro menschlicher Zelle,[10][6] davon etwa 2,800 Schäden der Art 8-oxoGua, 8-oxodG plus 5-HMUra.[11][12] In Ratten entstehen etwa 74.000 bis 100.000 pro Tag pro Zelle.[6][13][10] In Zellen von Mäusen entstehen zwischen 28.000 und 47.000 Schäden der Art 8-oxoGua, 8-oxodG, 5-HMUra.[12][11][14]

Durch Eisen(II)-Ionen (oder andere Übergangsmetalle) können Hydroxidradikale über die Fenton-Reaktion gebildet werden.[15] Dabei werden die Eisenionen zu Eisen(III)-Ionen oxidiert. Die Regeneration (Reduktion) erfolgt über die Haber-Weiss-Reaktion. Eisen ist das häufigste Übergangsmetall in den meisten Lebewesen.[16]

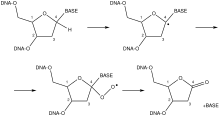

Hydroxidradikale können am 1'-C-Atom der Desoxyribose zur Bildung eines Radikals führen, das wiederum mit Sauerstoff ein Peroxid bildet, das sich zum 2’-Desoxyribonolacton umlagert und die Nukleinbase freisetzt, wodurch eine abasische Stelle in der DNA entsteht. Das 2’-Desoxyribonolacton ist mutagen und hemmt die DNA-Reparatur.[17]

Hydroxidradikale können auch an die π-Elektronen von bestimmten Doppelbindungen in Nukleinbasen addieren, unter anderem an C5-C6 von Pyrimidinen und N7-C8 in Purinen.[18] Daneben können Hydroxidradikale an verschiedene andere Atome in DNA addieren.

Depurinierung

Spontane Abspaltung einer Purinbase vom Zucker-Phosphat-Gerüst durch hydrolytische Spaltung der N-glycosidischen Bindung zwischen Purinbase und Desoxyribose. Das Phosphodiestergerüst bleibt dabei intakt und mit sogenannten apurinischen Stellen zurück. Depurinierungen kommen pro Tag pro Säugetierzelle etwa 2.000 bis 14.000 Mal vor.[19][20][21][22][23]

Depyrimidierung

Hydrolytische Abspaltung einer Pyrimidinbase vom Phosphodiestergerüst der DNA. Depyrimidierungen entstehen in einer Säugetierzelle etwa 600 bis 700 Mal täglich.[22][23]

Strangbrüche

Ein Einzelstrangbruch tritt etwa 55.200 Mal pro Tag pro Säugetierzelle auf.[23] Hydroxylradikale bevorzugen innerhalb der Ribose 5′ H > 4′ H > 3′ H ≈ 2′ H ≈ 1′ H als Reaktionspartner, was zum Strangbruch führen kann.[24]

Ein Doppelstrangbruch kommt pro Zellteilung pro menschlicher Zelle etwa 10 bis 50 Mal vor.[25][26]

Methylierung

Methylierte DNA-Basen sind N3-Methyladenin, N7-Methylguanin, O6-Methylguanin, N3-Methylcytosin, O4-Methylthymin, O4-Ethylthymin und N3-Methylthymin.[7] O6-Methylguanin entsteht in einer Säugetierzelle täglich etwa 3,120 Mal.[23] Die Desaminierung von Cytosin kommt pro Säugetierzelle pro Tag etwa 192 Mal vor.[23] Daneben kann auch M1dG (3-(2′-Desoxy-β-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)-pyrimido[1,2-a]-purin-10(3H)-on) gebildet werden.[27][28] M1G und 8-oxodG sind ihrerseits mutagen.[29][30]

Andere DNA-Addukte

Durch Mutagene können unterschiedliche DNA-Addukte gebildet werden.

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ Hochspringen nach: a b Clark Chen, Carol Bernstein, Anil R. Prasad,

Valentine Nfonsam, Harris Bernstein: New Research Directions in DNA Repair. Kapitel 16:

DNA Damage, DNA Repair and

Cancer. ISBN 978-953-511-114-6.

DNA Damage, DNA Repair and

Cancer. ISBN 978-953-511-114-6.

- ↑ Hochspringen nach: a

b Sung-Lim Yu, Sung-Keun Lee: Ultraviolet radiation: DNA damage, repair, and human disorders. In:

Molecular & Cellular Toxicology. 13, 2017, S. 21,

doi:10.1007/s13273-017-0002-0.

doi:10.1007/s13273-017-0002-0.

- ↑ Peter Elsner, Erhard Hoelzle

u. a.: Täglicher Lichtschutz in der Prävention chronischer UV-Schäden der Haut. In: JDDG. 5, 2007,

doi:

10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06099_supp.x.

10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06099_supp.x.

- ↑ J. A. Swenberg, K. Lu, B. C. Moeller, L. Gao, P. B. Upton, J. Nakamura, T. B. Starr: Endogenous versus exogenous

DNA adducts: their role in carcinogenesis, epidemiology, and risk assessment. In: Toxicol Sci. 120(Suppl 1), 2011, S. S130–S145.

PMID 21163908

PMID 21163908

- ↑ J. Nakamura, J. A. Swenberg: Endogenous apurinic/apyrimidinic sites in genomic DNA of mammalian tissues. In:

Cancer Research. 59(11), 1999, S. 2522–2526.

PMID 10363965

PMID 10363965

- ↑ Hochspringen nach: a b

c H. J. Helbock, K. B. Beckman, M. K. Shigenaga, P. B. Walter, A. A. Woodall, H. C. Yeo, B. N. Ames:

DNA oxidation matters: The HPLC-electrochemical detection assay of 8-oxo-deoxyguanosine and 8-oxo-guanine. In:

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA.

Band 95,

Nr. 1, 6. Januar 1998,

ISSN 0027-8424, S. 288–293,

doi:

10.1073/pnas.95.1.288,

10.1073/pnas.95.1.288,

PMID 9419368,

PMID 9419368,

PMC 18204 (freier Volltext).

PMC 18204 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Hochspringen nach: a b

c N. Chatterjee, G. C. Walker: Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. In: Environmental and molecular

mutagenesis. Band 58, Nummer 5, Juni 2017, S. 235–263,

doi:

10.1002/em.22087,

10.1002/em.22087,

PMID 28485537,

PMID 28485537,

PMC 5474181 (freier Volltext).

PMC 5474181 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ J. F. Ward: DNA damage produced by ionizing radiation in mammalian cells: identities, mechanisms of formation,

and reparability. In: Progress in nucleic acid research and molecular biology. Band 35, 1988, S. 95–125.

PMID 3065826.

PMID 3065826.

- ↑ M. L. Hamilton, Z. Guo, C. D. Fuller, H. Van Remmen, W. F. Ward, S. N. Austad, D. A. Troyer, I. Thompson, A.

Richardson: A reliable assessment of 8-oxo-2-deoxyguanosine levels in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA using the sodium iodide method to isolate DNA. In: Nucleic Acids Res.

29(10), 2001, S. 2117–2126.

PMID 11353081.

PMID 11353081.

- ↑ Hochspringen nach: a b B. N. Ames, M. K. Shigenaga, T. M. Hagen:

Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences USA. Band 90, Nr. 17, 1. September 1993,

ISSN 0027-8424, S. 7915–7922,

doi:

10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915,

10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915,

PMID 8367443,

PMID 8367443,

PMC 47258 (freier Volltext).

PMC 47258 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Hochspringen nach: a b M. Foksinski, R. Rozalski, J. Guz, B.

Ruszkowska, P. Sztukowska, M. Piwowarski, A. Klungland, R. Olinski: Urinary excretion of DNA repair products correlates with metabolic rates as well as with maximum life spans of

different mammalian species. In: Free Radic Biol Med. 37(9), 2004, S. 1449–1454.

PMID 15454284.

PMID 15454284.

- ↑ Hochspringen nach: a b B. Tudek, A. Winczura, J. Janik, A. Siomek,

M. Foksinski, R. Oliński: Involvement of oxidatively damaged DNA and repair in cancer development and aging. In: Am J Transl Res. 2(3), 2010, S. 254–284.

PMID 20589166.

PMID 20589166.

- ↑ C. G. Fraga, M. K. Shigenaga, J. W. Park, P. Degan, B. N. Ames: Oxidative damage to DNA during aging:

8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine in rat organ DNA and urine. In: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 87(12), 1990, S. 4533–4537.

PMID 2352934.

PMID 2352934.

- ↑ M. L. Hamilton, Z. Guo, C. D. Fuller, H. Van Remmen, W. F. Ward, S. N. Austad, D. A. Troyer, I. Thompson, A.

Richardson: A reliable assessment of 8-oxo-2-deoxyguanosine levels in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA using the sodium iodide method to isolate DNA. In: Nucleic Acids Res.

29(10), 2001, S. 2117–2126.

PMID 11353081.

PMID 11353081.

- ↑ E. S. Henle, S. Linn: Formation, prevention,

and repair of DNA damage by iron/hydrogen peroxide. In: The Journal of biological chemistry. Band 272, Nummer 31, August 1997, S. 19095–19098.

PMID 9235895.

PMID 9235895.

- ↑ W. K. Pogozelski, T. D. Tullius: Oxidative Strand Scission of Nucleic Acids: Routes Initiated by Hydrogen Abstraction from the Sugar Moiety. In: Chemical Reviews. Band 98, Nummer 3, Mai 1998, S. 1089–1108. PMID 11848926.

- ↑ J. Lhomme, J. F. Constant, M. Demeunynck: Abasic DNA structure, reactivity, and recognition. In:

Biopolymers. Band 52, Nummer 2, 1999, S. 65–83,

doi:

10.1002/1097-0282(1999)52:2<65::AID-BIP1>3.0.CO;2-U.

10.1002/1097-0282(1999)52:2<65::AID-BIP1>3.0.CO;2-U.

PMID 10898853.

PMID 10898853.

- ↑ Steen Steenken: Purine bases, nucleosides, and nucleotides: aqueous solution redox chemistry

and transformation reactions of their radical cations and e- and OH adducts. In: Chemical Reviews. 89, 1989, S. 503–520,

doi:10.1021/cr00093a003.

doi:10.1021/cr00093a003.

- ↑ T. Lindahl, B. Nyberg: Rate of depurination of native deoxyribonucleic acid. In: Biochemistry. 11(19),

1972, S. 3610–3618.

doi:10.1038/362709a0

doi:10.1038/362709a0

PMID 4626532.

PMID 4626532.

- ↑ T. Lindahl: Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. In: Nature. Band 362, Nummer 6422,

April 1993, S. 709–715,

doi:10.1038/362709a0,

doi:10.1038/362709a0,

PMID 8469282 (Review).

PMID 8469282 (Review).

- ↑ J. Nakamura, V. E. Walker, P. B. Upton, S. Y. Chiang, Y. W. Kow, J. A. Swenberg: Highly sensitive

apurinic/apyrimidinic site assay can detect spontaneous and chemically induced depurination under physiological conditions. In:

Cancer Research. Band 58, Nummer 2, Januar 1998, S. 222–225.

PMID 9443396.

PMID 9443396.

- ↑ Hochspringen nach: a b T. Lindahl: DNA repair enzymes acting on spontaneous lesions in DNA. In: W. W. Nichols, D. G. Murphy (Hrsg.): DNA Repair Processes. Symposia Specialists, Miami 1977, ISBN 0-88372-099-X, S. 225–240.

- ↑ Hochspringen nach: a b c d e R. R. Tice, R. B. Setlow: DNA repair and replication in aging organisms and cells. In: E. E. Finch, E. L. Schneider (Hrsg.): Handbook of the Biology of Aging. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York 1985, ISBN 0-442-22529-6, S. 173–224.

- ↑ B. Balasubramanian, W. K. Pogozelski, T. D. Tullius: DNA strand breaking by the hydroxyl radical is governed by

the accessible surface areas of the hydrogen atoms of the DNA backbone. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Band 95, Nummer 17, August 1998, S. 9738–9743.

PMID 9707545,

PMID 9707545,

PMC 21406 (freier Volltext).

PMC 21406 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ J. E. Haber: DNA recombination: the replication connection. In: Trends Biochem Sci. 24(7), 1999,

S. 271–275.

PMID 10390616.

PMID 10390616.

- ↑ M. M. Vilenchik, A. G. Knudson: Endogenous DNA double-strand breaks: production, fidelity of repair, and

induction of cancer. In: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100(22), 2003, S. 12871–12876.

PMID 14566050.

PMID 14566050.

- ↑ S. W. Chan, P. C. Dedon: The biological and metabolic fates of endogenous DNA damage products. In:

J Nucleic Acids. 2010, S. 929047.

PMID 21209721

PMID 21209721

- ↑ F. F. Kadlubar, K. E. Anderson, S. Häussermann, N. P. Lang, G. W. Barone, P. A. Thompson, S. L. MacLeod, M. W. Chou,

M. Mikhailova, J. Plastaras, L. J. Marnett, J. Nair, I. Velic, H. Bartsch: Comparison of DNA adduct levels associated with oxidative stress in human pancreas. In:

Mutat Res. 405(2), 1998, S. 125–133.

PMID 9748537

PMID 9748537

- ↑ L. A. Vander-Veen, M. F. Hashim, Y. Shyr, L. J. Marnett: Induction of frameshift and base pair substitution

mutations by the major DNA adduct of the endogenous carcinogen malondialdehyde. In: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100(24), 2003, S. 14247–14252.

PMID 14603032

PMID 14603032

- ↑ X. Tan, A. P. Grollman, S. Shibutani: Comparison of the mutagenic properties

of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyadenosine and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine DNA lesions in mammalian cells. In: Carcinogenesis. 20(12), 1999, S. 2287–2292.

PMID 10590221

PMID 10590221

© biancahoegel.de

Datum der letzten Änderung: Jena, den: 25.03. 2025